The Future is Beige

In 1995, the future didn’t arrive in a silver jumpsuit. No, the future arrived in a London hotel conference suite in the form of a diminutive young man who looked like he’d been dressed by a librarian working to a budget of nothing.

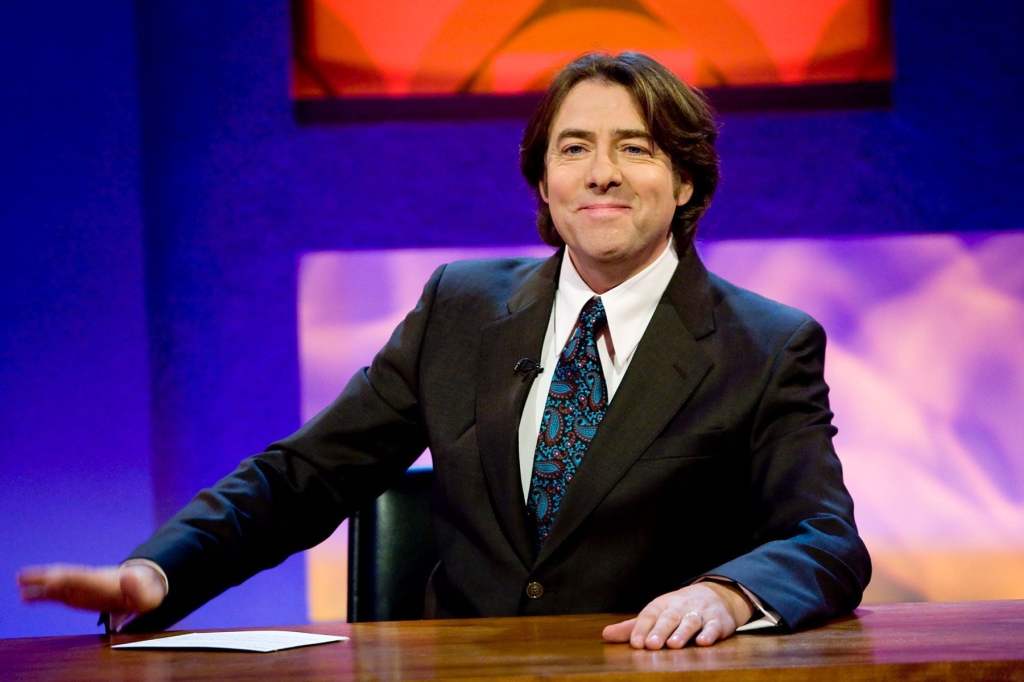

I had been tasked with booking the celebrity faces required to promote the UK launch of Microsoft Windows 95. Back then, celebrity was my business as well as an unhealthy national obsession (still is). I had assembled a glittering pantheon of British establishment icons: David Gower, the epitome of effortless cricketing grace; Angela Rippon, the poised voice of national authority; Jonathan Ross, the sharp-suited vanguard of ’90s cool. We had Carol Vorderman, the human calculator; children’s favourite Andy Crane; David Emanuel, fashion designer to British royalty. These guys were luminaries of the analogue age; high-def personalities who commanded the attention of a room simply by strolling in.

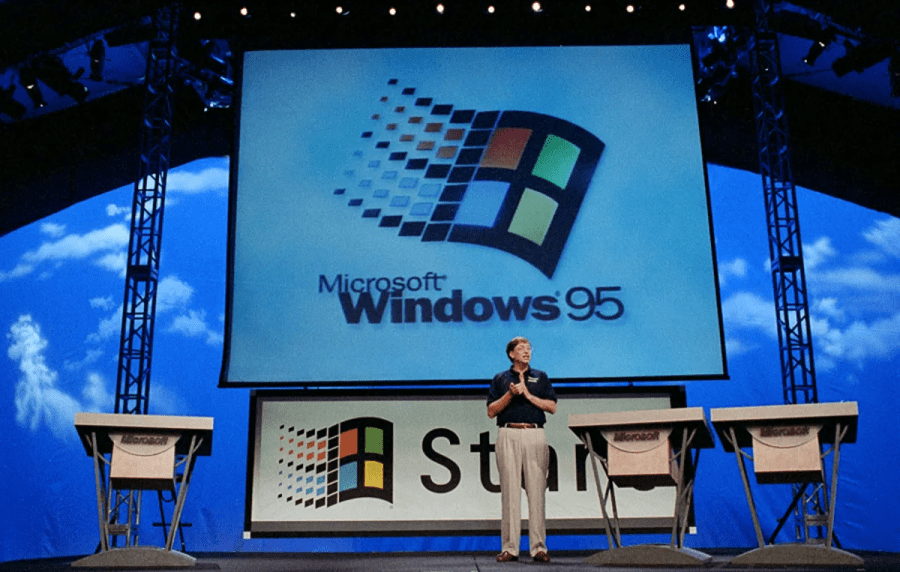

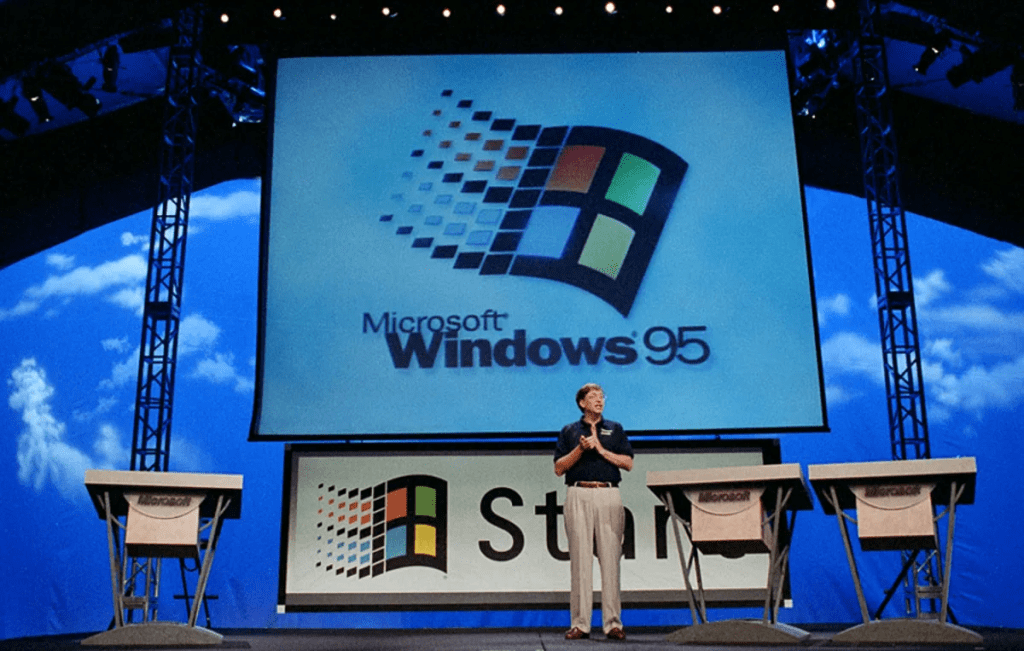

Then there was low-def Bill Gates. Underwhelming doesn’t quite capture the drabness. In a room full of people who were professionally charismatic, Bill Gates was a sartorial vacuum. He was the walking-talking cliché of a cardigan-clad nerd before the world realised that nerds were about to become the global aristocracy.

Bill Gates opted for tones of weak tea, or more accurately, a shade of diarrhoea-brown that seemed designed to blend into the podium’s furniture. The single nod to his success; the aspect of the man that will forever stick in my mind; an embroidered BG on the collar-tip of his badly pressed shirt.

Here was the wealthiest man on the planet, carrying himself with the disregarding confidence of a man who knew he owned the future. While my celebrities were the face of the present, the man in the beige trousers was the architect of their obsolescence. Bill wasn’t there to join our world; he was there to consign it to history.

A Failed Connection

Equally unengaging was Bill’s techno-spiel. Imagine sitting in a darkened room while a man with the nasal range of a dial-up modem explains that your life is about to change forever. Bill spoke of “e-messages” and a “World Wide Web”; an “information superhighway” that would allow an entrepreneur in Penzance to trade with a merchant in Manila.

At the time, all this sounded like pure science fiction. We liked Microsoft Word because it meant we didn’t have to use Tipp-Ex on our typewriters. But this Internet contrivance felt like a solution in search of a problem. In 1995, only Marks and Spencer, Barclays, and Littlewoods had websites, and even those were little more than digital posters. You couldn’t do anything with them. And since I didn’t bank with Barclays, the whole thing felt like a pipedream for people with too much time and money.

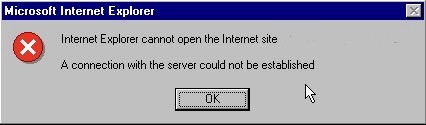

The demonstration itself was a comedy of errors. Tedious hours ground by as Bill droned on with his barely containable speculation about unlikely applications, predicting the whole world will soon be working this way, even though, with much clicking, he failed to secure any type of connection to this ‘internet’ contrivance he so commended. He clicked. He waited. The equipment declined to cooperate. We shuffled in our seats, hiding our smirks.

We were issued with exclusive @msn.com “e-message” addresses; pointless strings of characters because no one else in our universe had one. We could only communicate with each other, Microsoft employees, or Bill himself. We pocketed our considerable cheques and went back to our analogue lives; failing to realise we were witnessing the first, messy, stuttering heartbeat of the unrecognisable world we inhabit today, and blissfully unaware that the world we knew was about to be deleted.

Then Bill Gates was Dead Wrong

By the time the Windows 98 launch rolled around, Bill Gates wasn’t just a nerd anymore; he was a prophet billionaire nerd. When he spoke, the markets moved. When he pointed, the tech world marched. And at that time, he pointed confidently at the printer.

Bill’s prediction was that photo-quality printing would be the “next big thing.” He envisioned a world where every household would become a miniature Kodak lab. We’d all be sitting at home, whirring away, churning out glossy 6x4s of our holidays and Sunday roasts. He was dead wrong.

What Bill failed to see was that the screen itself would become the destination. The photo-quality display didn’t just compete with the printer; it murdered it. We didn’t want a physical copy of every fleeting moment; we wanted the instant, backlit gratification of the pixel. Your printer became a dusty relic, a temperamental box in the corner of the room that only comes to life when a boarding pass or a postage label is required.

Bill’s fallibility is important. It proves that while tech giants can build and develop, they don’t always know where the users will want to go. Bill thought the future was more paper. The reality was that we wanted less paper, but better quality.

Sitting on the Dock of the Bay – Wasting Time

Back to 1995. Armed with limitless free Microsoft software and a slightly nerdy streak, I undertook to waste some time building a pointless website for my celebrity agency.

But it wasn’t pointless; it was an apprenticeship I didn’t know I needed. Bill was right about the importance of the infrastructure, even if he missed the mark on the hardware. A few decades later, we all rely upon a web presence – even a little publishing house like M2M Books.

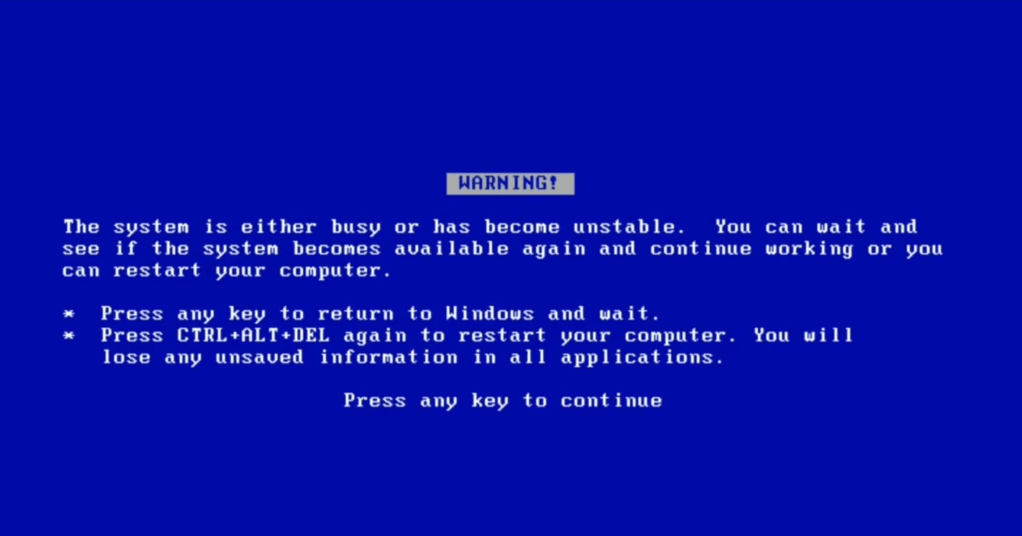

So, here I go again, editing and growing yet another website. It is a daunting prospect, but creating this content is proving considerably less taxing than the technical grapple of the mid-nineties. I don’t miss the blue-screen-inducing, instruction-manual-crunching nightmare of FrontPage 1.0. Code-editing back then felt like performing surgery with a blunt spoon, requiring the patience of a saint and the vocabulary of a sailor.

Today

If Bill had been right about photo-quality printing, today’s world would be buried in a landslide of cheap, glossy nonsense. Instead, because the screen took over the disposable side of our lives; the news, the gossip, the quick snaps; fast-evolving technologies have left a sacred, more valued space for the material object. Good news for books!

So, being an independent press today means we don’t need to compete with the screen; we can complement it. I know you’re reading my words on a high-definition display that would have made 1995 Bill Gates weep with joy. But I also know that when you close this tab, you may want something in your hands that has weight, texture, and a soul. A book! Bill’s printer fallacy informed us that paper remains our preferred choice for literature.

M2M Books can operate as an independent press largely because Bill’s unlikely applications actually worked. The technology that seemed so ridiculous in that London hotel suite eventually dismantled the publishing gatekeepers. Back then, writers needed a massive corporate house to get a story told. Now, the artisan press thrives because we can bypass the usual suspects. We use the tools Bill pioneered to ensure that the analogue soul of a good book; the weight of the paper, the smell of ink, the craft of the word; can reach a global audience without needing a nod from a corporate giant. Bill might have been fallible about printers, but he gave us the keys to the kingdom.

Gareth James – Chief Reader M2M Books

Hope you like the new look website. It’s been a circuitous thirty years in the making 👍🏾 please subscribe and share👇🏾